Ulrich Zwingli 1484 - 1531

While Luther was busy battling the papal emissaries and civil authorities in Germany, Catholic priest Ulrich Zwingli (1484-1531) started his reform movement in Zurich, Switzerland. That area being German-speaking, the people were already affected by the tide of reform from the north. Around 1519, Zwingli began to preach against indulgences, Mariolatry, clerical celibacy, and other doctrines of the Catholic Church. Though Zwingli claimed independence from Luther, he agreed with Luther in many areas and distributed Luther’s tracts throughout the country. In contrast with the more conservative Luther, however, Zwingli advocated the removal of all vestiges of the Roman Church—images, crucifixes, clerical garb, even liturgical music. A more serious controversy between the two Reformers, however, was on the issue of the Eucharist, or Mass (Communion). Luther, insisting on a literal interpretation of Jesus’ words, ‘This is my body,’ believed that the body and blood of Christ were miraculously present in the bread and wine served at Communion. Zwingli, on the other hand, argued, in his treatise On the Lord’s Supper, that Jesus’ statement “must be taken figuratively or metaphorically; ‘This is my body,’ means, ‘The bread signifies my body,’ or ‘is a figure of my body.’” Because of this difference, the two Reformers parted ways. Zwingli continued to preach his reform doctrines in Zurich and effected many changes there. Other cities soon followed his lead, but most people in the rural areas, being more conservative, clung to Catholicism. The conflict between the two factions became so great that civil war broke out between Swiss Protestants and Roman Catholics. Zwingli, serving as an army chaplain, was killed in the battle of Kappel, near the Lake of Zug, in 1531. When peace finally came, each district was given the right to decide its own form of religion, Protestant or Catholic. Luther and Zwingli had paved the way towards this belief with their 'faith alone' principle, and their persistent affirmation of salvation as a gift from God that cannot be earned by human effort. But neither reformer had dealt with this implicit concept of election thoroughly or systematically. Calvin, in contrast, embraced the logical conclusion of sola fide, sola gratia, and made God's overwhelming agency the very structure of his systematic theology, passing on to his disciples a firm, strident belief in election and predestination. The earliest Anabaptists—in this case, members of the group that historians have come to call the Swiss Brethren—insisted that the Bible alone was the basis for their beliefs and practices. They correctly claimed that scripture included no direct mandate for infant baptism; Zwingli defended it by analogy to the Jewish practice of circumcision. But however biblical their view, it was defined as illegal by local authorities and thereby became a 'radical' position, their insistence on believers' baptism a 'radical' practice.

'Protestatio' at Diet of Speyer gives its name to 'Protestants'; failure of Luther and Zwingli to agree over Eucharist at Colloquy of Marburg; first religious war in Switzerland

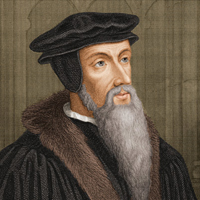

John Calvin 1509 -1564

"We assert, that by an eternal and immutable counsel, God has once for all determined, both whom He would admit to salvation, and whom He would condemn to destruction. We affirm that this counsel, as far as concerns the elect, is founded on His gratuitous mercy, totally irrespective of human merit; but that to those whom He devotes to condemnation, the gate of life is closed by a just and irreprehensible, but incomprehensible, judgment."

The austerity of such a teaching is also reflected in other areas. Calvin insisted that Christians must live holy and virtuous lives, abstaining not only from sin but also from pleasure and frivolity. Further, he argued that the church, which is made up of the elect, must be freed of all civil restrictions and that only through the church can a truly godly society be established. Shortly after publishing Institutes, Calvin was persuaded by William Farel, another Reformer from France, to settle in Geneva. Together they worked to put Calvinism into practice. Their aim was to turn Geneva into a city of God, a theocracy of God-rule combining the functions of Church and State. They instituted strict regulations, with sanctions, covering everything from religious instruction and church services to public morals and even such matters as sanitation and fire prevention. A history text reports that "a hair-dresser, for example, for arranging a bride's hair in what was deemed an unseemly manner, was imprisoned for two days; and the mother, with two female friends, who had aided in the process, suffered the same penalty. Dancing and card-playing were also punished by the magistrate." Harsh treatment was meted out to those who differed from Calvin on theology, the most notorious case being the burning of Spaniard Miguel Serveto, or Michael Servetus. Calvin continued to apply his brand of reform in Geneva until his death in 1564, and the Reformed church became firmly established. Protestant reformers, fleeing persecution in other lands, flocked to Geneva, took in Calvinist ideas, and became instrumental in starting reform movements in their respective homelands. Calvinism soon spread to France, where the Huguenots (as the French Calvinist Protestants were called) suffered severe persecution at the hands of the Catholics. In the Netherlands, Calvinists helped establish the Dutch Reformed Church. In Scotland, under the zealous leadership of the former Catholic priest John Knox, the Presbyterian Church of Scotland was established along Calvinist lines. Calvinism also played a role in the Reformation in England, and from there it went with the Puritans to North America. In this sense, although Luther set the Protestant Reformation in motion, Calvin had by far the greater influence in its development.

Giovanni Valentino Gentile

c.1520 – 1566